During a 1911 journey—in which they would discover Machu Picchu—Hiram Bingham’s exploration party came across some native Peruvians who “lived almost entirely on gruel made from chuño, frozen bitter potatoes. Little else than potatoes will grow at 14,000 feet above the sea.”[1] As the accompanying photograph shows, chuño can still be purchased in farmers markets in the Cusco region of Peru.[2]

During a 1911 journey—in which they would discover Machu Picchu—Hiram Bingham’s exploration party came across some native Peruvians who “lived almost entirely on gruel made from chuño, frozen bitter potatoes. Little else than potatoes will grow at 14,000 feet above the sea.”[1] As the accompanying photograph shows, chuño can still be purchased in farmers markets in the Cusco region of Peru.[2]

For millennia, those living in the Andean highland regions of Bolivia and Peru carefully tended to and cultivated over 3000 varieties of potatoes, many of which remain unknown to our collective palates today. The Central Restaurante in Lima, Peru, however, features chuño recipes in its menu offerings.

Chef Virgilio Martinez leaves the "potatoes in the snow overnight; by the time the sun comes up, the potatoes have dried out. 'When you see them, they look like white-peeled potatoes, like flour or something. They aren't heavy at all, either, because they lose their water, Martinez says, also noting they can be stored for up to 10 years."[3]

Like their Andean predecessors, modern day inventors continue to slice, dice, freeze, bake, dehydrate, fry and otherwise manipulate the characteristics of the humble potato in patentable ways. This brief article examines some recently issued U.S. patents to determine what they disclose about the technological art of processing potatoes.

"Baked Potato Chunks"

U.S. Patent No. 8,329,244 (issued on 12/11/12) discloses a process for creating a new form of potato product for frozen distribution. It is entitled "Friable, Baked Potato Pieces and Chunks." The process involves fully baking a potato and then breaking it into pieces suitable for frying. The inventors sought "a potato product that has baked as well as fried flavors." Per the '244 patent specification, no such potato product previously existed before this invention.

The '244 patent describes its unique potato product as follows:

[B]ite-sized pieces of optimally-baked potato [retain] the taste and texture of both the skin and pulp portions. The product exhibits a fully-baked potato flavor, texture and aroma, and it can be prepared simply for serving in any portion size with a minimum of effort. The texture of the product will include a characteristic dry, fluffy, mealy texture for the pulp on the interior of the potato and will have skin attached to unmashed pulp of the potato. The pulp will offer some resistance to the bite but will quickly become smooth like mashed potatoes when masticated.

In marketing language, the '244 patent's assignee—the Nonpariel Corporation—touts its "Betty Crocker" branded product as bringing "you a family favorite – baked potatoes – in a fast, easily prepared, and delicious form. We start with only the finest potatoes, bake them, chop them into chunks, and finally quick-freeze them. Our “Baked Potato Chunks” are fully cooked, ready to “heat eat”." See http://www.nonpareilbrand.com/frozen.php.

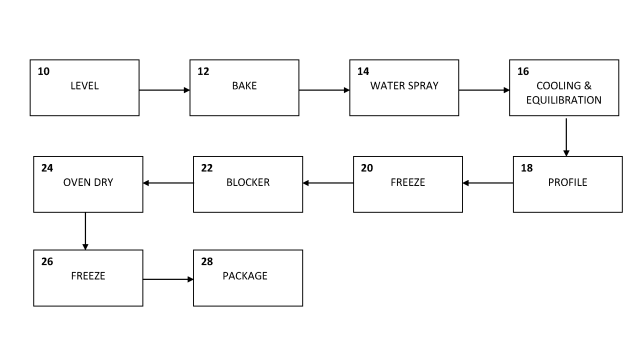

Interestingly enough, the '224 patent's block diagram itself displays the many means of processing potatoes that find their historical roots in the Andean cultivation of potatoes. This diagram represents the '244 patent's preferred processing method:

"Dehydrated Potato Flakes"

When it owned the Pringles potato chip brand, Proctor & Gamble invested time and effort in advancing potato processing technology. One illustrative example is U.S. Patent No. 7,998,522, entitled "Dehydrated Potato Flakes" (issued on 8/16/11). The '522 patent describes the difficulties faced in conventional potato processing and how they were surmounted by the present invention:

The physical properties necessary in a flake used to formulate a dough for making fabricated farinaceous [i.e., made from or rich in starch] products have gone unrecognized or unappreciated. While conventional processes try to minimize broken cells, it has been found that flakes comprising from about 40% to about 60% broken cells are desirable from a sheeting standpoint. Further, it has been found that controlling the difference between hot paste viscosity and cold paste viscosity improves processability, even though conventional processes do not place any importance on this particular physical property. It has also been found that a low water absorption is desirable in a flake used for making a dough. While conventional processes suggest a high water absorption index is desirable.

Conventional methods for processing potatoes into dehydrated products have not allowed potato processors to produce suitable flakes from potatoes of different variety, different compositions or from potato by-products (e.g., potato pieces left over from French fry processes) or potatoes from the beginning and end of season. Even when the same variety of potatoes are [sic] used, there is an inability to consistently control the physical properties of the flakes by processing.

When Kellogg acquired "Pringles" from Proctor & Gamble in June 2012, it appears to have acquired P&G's associated patent portfolio. One of the '522 inventors, Maria Dolores Martinez-Serba Villagran, would become a first named inventor of U.S. Patent No. 8,440,251, entitled "Doughs Containing Dehydrated Potato Products" (issued on 5/14/13) and assigned to Kellogg North America Company.

The object of the '251 invention is a process for producing quality doughs and finished products from "non-ideal potato products." The specification describes the problematic issue meant to be solved:

For snacks, especially snacks made from sheeted doughs, the quality of the dough determines the efficiency and reliability of the production process, and the quality of the finished product. It is known that doughs comprising potato flakes, having from 40% to 60% broken cells and from 16% to 27% free amylose, process well and result in god [sic] quality finished products. Unfortunately, such dehydrated potato products typically command a premium price and, in many geographies, are in limited supply. As a result, there have been attempts to produce doughs from non-ideal dehydrated potato products.

The '251 inventors believed they discovered the "root causes" impeding the use of "non-ideal" dehydrated potato products. Product quality issues were related to the "amount and type of free starch, free cell wall components and starch-lipid complexes found in such non-ideal dehydrated potato products." Having identified these root causes, the inventors were then "able to identify materials that, when combined with non-ideal flakes, eliminate the root causes of said quality problems."

A Cutting Edge Potato Chip

Who hasn't put off by the unsatisfactory mouth feel and texture of baked potato chips?

U.S. Patent No. 8,163,321 (issued on 4/24/12) addresses the consumer desire for less fatty, but crispy potato chips. Typically, when potato chips are fried by being submerged in hot oil, the "free" water in the chip is exchanged with the hot oil, resulting in a chip with higher fat content. Efforts to reduce this fat content by baking the potato chips have had less than desirable results:

[L]ow fat baked potato chips, while achieving a lower fat content than traditional potato chips, are very dry and flinty in texture. Also, these traditional baked potato chips have a poor mouthfeel and do not taste much like a traditional fried potato chip because they do not contain the fat of traditional potato chips. Additionally, these traditional low fat baked potato chips break very easily during handling, for example, during packaging, distribution, and consumption. Upon opening a bag of traditional low fat baked potato chips, the consumer is generally dissatisfied with the number of broken potato chip pieces, commonly referred to as crumbs.

The '321 patent inventors solve this problem by first applying a coating composition (a "wet slurry") to the potato chip before it is fried. The coating sets quickly when fried and partially insulates the potato substrate from absorbing hot cooking oil. The coating is typically clear and substantially invisible to the consumer, and thus does not detract from the potato chip's appearance. Besides providing a better mouth feel and texture, the '321 patented process retards staleness. The coating enhances the tensile strength of the potato chip, thereby increasing its resistance to breakage.

Fifty Different Ways to Prepare Spuds

At the Centrale Restaurante in Lima, you will find that Chef Martinez "and his team employ more than 50 different techniques to prepare spuds. The purée them, fry them, dry them, and make infusions, thickeners, and jellies. They also ferment the skins."[4]

While American consumers may not be nearly so adventurous in their potato recipes as Peruvians, a hallmark of the American diet — the potato chip — is still a vital object of inventive study and ingenuity.

___________________

[1] Hiram Bingham, Inca Land: Explorations in the Highlands of Peru (originally published in 1922). It was republished by the National Geographic Society in 2003.

[2] Chuño” by Eric in SF – Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Chu%C3%B1o.jpg#/media/File:Chu%C3%B1o.jpg.

[3] E. Goldberg, "This Restaurant Uses 50 Different Methods to Cook Potatoes," Bon Appétit (October 27, 2015).

[4] Id.